Bridging the gap: How Text-to-SQL is Changing Database Queries

Some people look surprised when they learn which programming language is the most used in today’s industry: believe it or not, it's SQL. According to the 2024 edition of IEEE’s programming languages ranking, SQL is the language most sought after by employers, closely followed by Python and Java. This trend, we think, can be attributed to two main factors: the continuous rise of cloud-based system architectures, and a general lack of deep technical knowledge among end users who still need access to data insights.

So how do LLMs come into play? Large language models have demonstrated high coding capabilities, even in the most esoteric and cryptic languages. Considering SQL’s relatively high-level syntax, in this blog post we’ll try to answer the following question: can LLMs write correct, effective, and meaningful SQL queries? Short answer: Yes – with a little help from some cutting-edge prompt engineering techniques.

Challenges in Text-to-SQL with LLMs

Among all the testing we have done, we found two main challenges when trying to get a LLM to write SQL code:

Contextual understanding: we have all encountered the problem of trying to understand an ambiguous question somebody asked us, and LLMs face this, too. When converting text queries to SQL code, it is important to identify exactly what information is being asked and how it can be translated to the information contained in the database. For example, imagine someone asked you for the top-selling bike in a shop: Would you consider this to be by quantity sold or by revenue?

Schema comprehension: to write meaningful SQL code, one must first know where to look for the answers. Databases can be huge, often containing an enormous amount of data with complex relationships and weirdly named tables and columns. This is one of the first obstacles we found when trying to implement our own text-to-SQL agent: how can we help (or make) the agent understand the database schema without hallucinating?

To overcome these challenges, we chose to use prompt engineering as our primary approach.

The Importance of Precise Prompt Engineering

One often tends to overestimate the capabilities of LLMs to completely understand the depths of a natural language prompt. Because of this, it is not uncommon to see someone spitting a horrendously written prompt on ChatGPT, and, surprisingly, still get a relatively decent answer. This doesn’t happen when one is trying to implement robust and stable agents capable of writing industry-level code that gets real meaningful insights.

In fact, among different text-to-SQL benchmarks, prompt engineering models are the ones often leading in the top ten positions. This highlights two main things: first, how accessible and adaptable prompt engineering can be; and second, the substantial improvement in results that prompt engineering offers. With the right approach, prompt engineering transforms LLMs from general-purpose assistants to highly specialized tools capable of meeting demanding SQL generation requirements.

Approach

Mixing some of our own ideas with the recommendations from the top-performing papers, we came up with the following prompt engineering model:

- Divide and conquer: understanding that agents can often hallucinate when given long instructions, we divided the SQL query generation process into three distinct stages, assigning each task to a specialized agent.

- Precision is key: we cannot stress enough the importance of structuring correctly the instructions given to the agent. In particular, we found that using delimiters, clear examples, and step-by-step guidance helped each agent stay focused and reduce errors.

- Clarity through structure: with the latest structured-output capabilities of advanced LLMs, we found that enforcing a format for sine agent’s responses significantly improved stability and precision.

Results

To explore whether LLMs can effectively serve as query writers, we conducted an initial evaluation of our approach. As of November 2024, in the last iteration of our development, this approach got us an exact match accuracy —where generated SQL queries matched expected results exactly��� of 89% across 100 randomly selected questions from the first Spider Benchmark, a well-regarded dataset for evaluating text-to-SQL models (See Spider: Yale Semantic Parsing and Text-to-SQL Challenge for more information). This, in fact, would have placed us in second place, just behind the “MiniSeek” paper.

Insights into Examples, Achievements, and Challenges

Our model’s performance with text-to-SQL queries shows both its strengths and areas where improvement is needed. Below are examples that illustrate correct query generation as well as cases that reveal limitations.

1. Our model didn't seem to struggle that much writing relatively complex queries:

Question: what is the number of routes operated by the airline American Airlines whose destinations are in Italy?

Goal query:

SELECT count(*)

FROM routes AS T1

JOIN airports AS T2

ON T1.dst_apid = T2.apid

JOIN airlines AS T3

ON T1.alid = T3.alid

WHERE T2.country = 'Italy'

AND T3.name = 'American Airlines'

Generated query:

SELECT COUNT(routes.rid)

FROM routes

JOIN airlines

ON routes.alid = airlines.alid

JOIN airports

ON routes.dst_apid = airports.apid

WHERE airlines.name = 'American Airlines'

AND airports.country = 'Italy';

2. Some ambiguous questions were marked as incorrect, though the answer was not completely wrong:

Question: what are the distinct names of wines with prices higher than any wine from John Anthony winery.

Goal query:

SELECT DISTINCT Name

FROM WINE

WHERE Price > (

SELECT min(Price)

FROM wine

WHERE Winery = "John Anthony")

Generated query:

SELECT DISTINCT wine.Name

FROM wine

WHERE wine.Price > (

SELECT MAX(wine.Price)

FROM wine

WHERE wine.Winery = 'John Anthony')

3. A clear limitation of our model was writing queries that involved specific keyword matching:

Question: how many animal type allergies exist?

Goal query:

SELECT count(*)

FROM Allergy_type

WHERE allergytype = "animal"

Generated query:

SELECT COUNT(*)

FROM Allergy_Type

WHERE AllergyType = 'Animal'

4. A few times, the model appeared to hallucinate, generating overly complex queries for questions that required much simpler solutions:

Question: what is the number of branches that have more than the average number of memberships?

Goal query:

SELECT count(*)

FROM branch

WHERE membership_amount > (

SELECT avg(membership_amount)

FROM branch)

Generated query:

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT branch.Branch_ID)

FROM branch

JOIN membership_register_branch

ON branch.Branch_ID = membership_register_branch.Branch_ID

GROUP BY branch.Branch_ID

HAVING COUNT(membership_register_branch.Member_ID) > (

SELECT AVG(member_count)

FROM (

SELECT COUNT(membership_register_branch.Member_ID) AS member_count

FROM membership_register_branch

GROUP BY membership_register_branch.Branch_ID

)

);

Going Beyond Academic Benchmarks

While academic evaluations provide valuable insights, they often fall short of addressing the necessities and complexities of real-world industry applications. For instance, a quick look at the testing databases of this project reveals its limitations: they lack the diversity, scale, and complexity typical of production-level industry databases. However, this doesn't diminish the validity of our findings. LLMs have demonstrated the potential to generate industry-grade SQL queries. Still, the effectiveness of any approach depends heavily on the unique characteristics of the database, such as its size, schema complexity, naming conventions, data sparsity, relationship depth, and even the consistency of its documentation.

Try It Out for Yourself

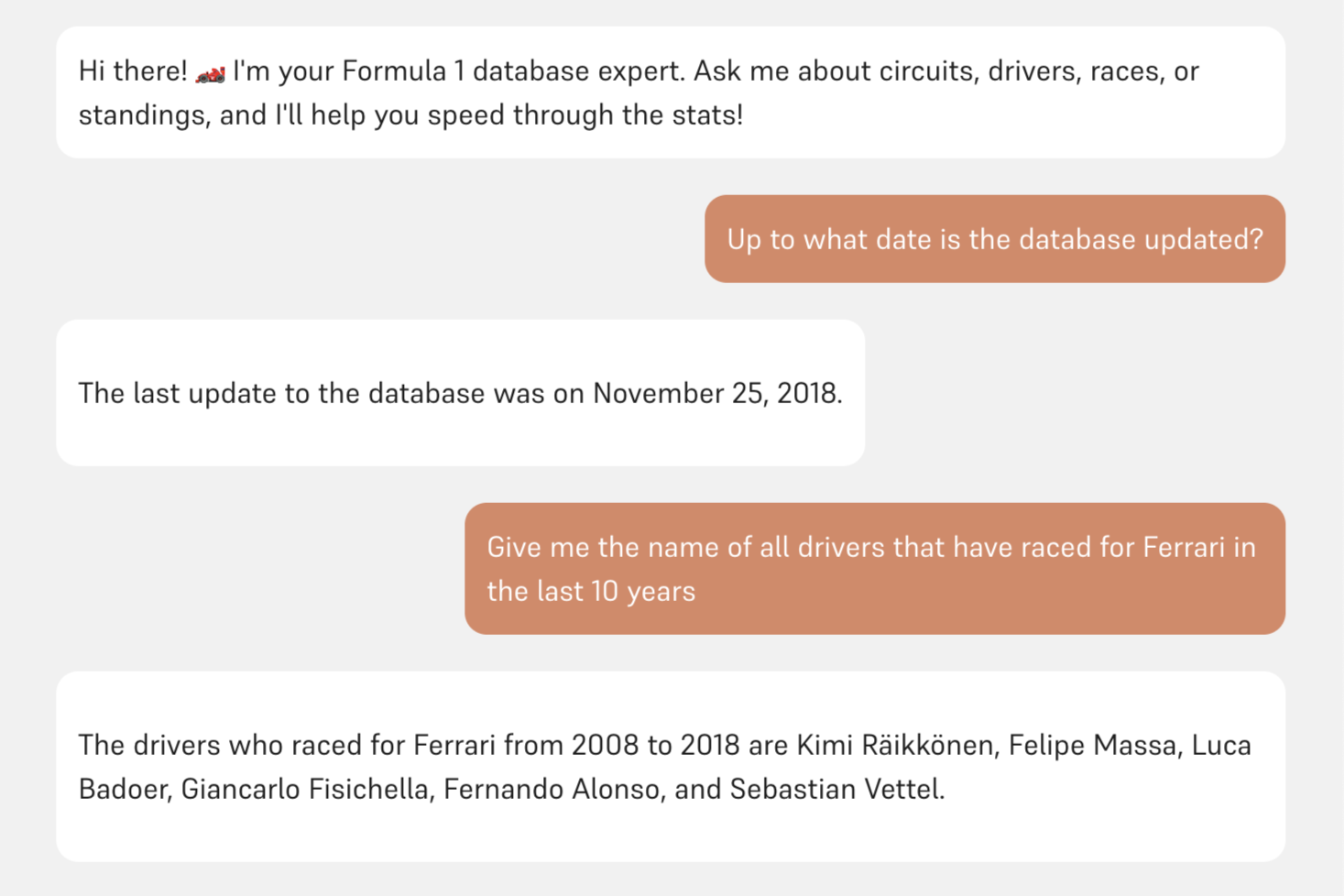

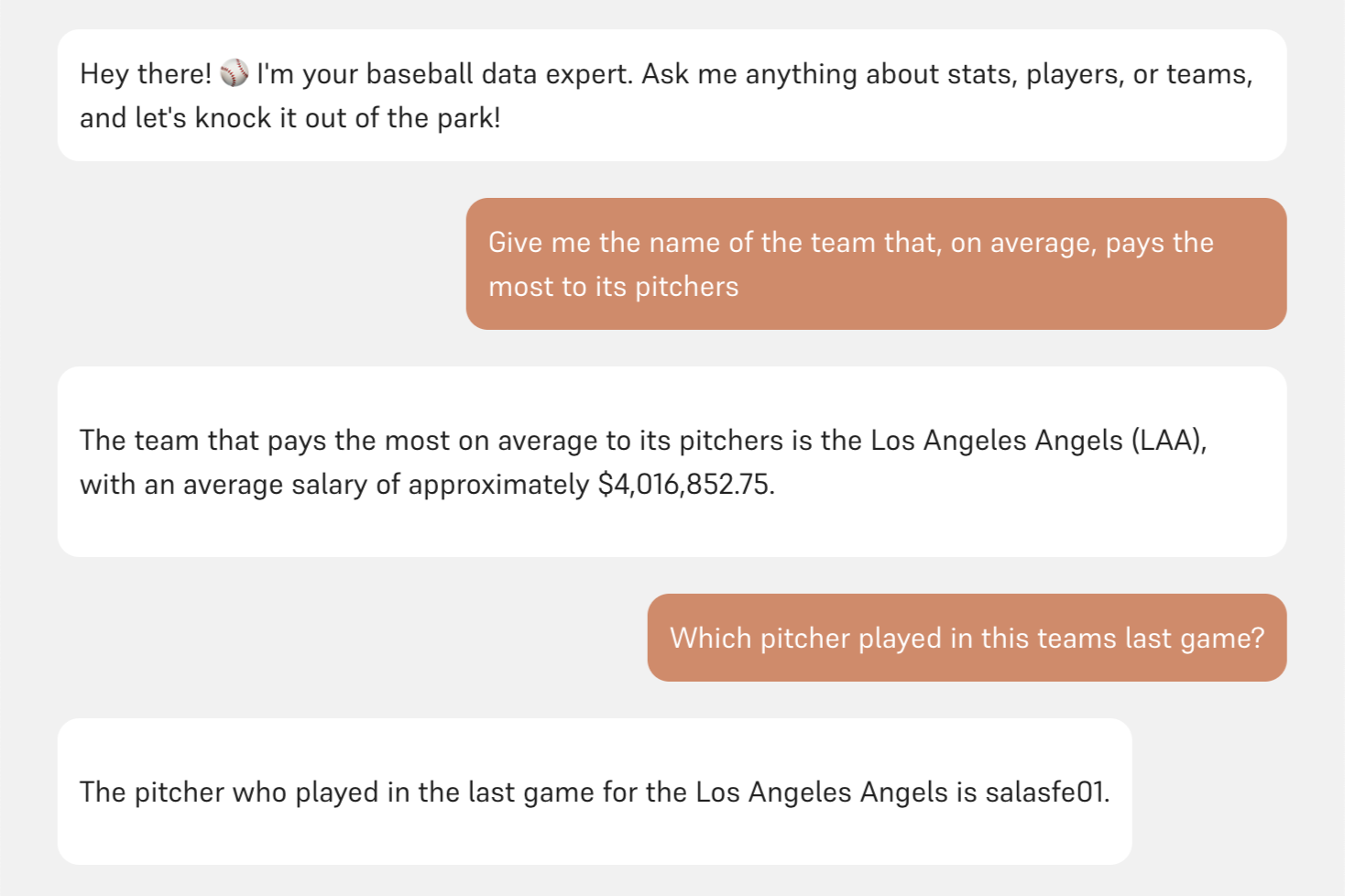

Curious to see the model in action? We've set up a few interactive demos at hal9's website, where you can explore its capabilities by asking questions about a sample database. This is your chance to test its strengths, uncover its limitations, and see how well it handles different types of queries. Whether you're looking for simple counts or more complex aggregations, the demo is a great way to get hands-on experience with text-to-SQL in a real-world context.

Baseball Database: This agent answers questions about a baseball database. It contains a total of 26 tables with 553,693 rows; including information about players, teams, awards, and game statistics. Feel free to try it in this link.

Formula 1 Database: This agent answers questions about a formula 1 database. It contains a total of 13 tables with 88,380 rows; including circuits, races, drivers, constructors, and seasons. It tracks results, standings, qualifying rounds, lap times, and pit stops, providing a full view of the performance and status of drivers and teams across F1 history. You can try it here.